Exit Note by Dorian Bridges

I left the club for an hour to finish reading it. now I yearn to yap about it. (Spoilers, obviously)

I absolutely adore Dorian Bridges. I read his second book, ‘Millennium Gothic’ and he was very quickly added to my list of my favourite writers. This past Friday, Bridges’ released his third book ‘Exit Note’, which was initially intended to be released posthumously, as an explanation for why Bridges’ would not be here anymore. I know it’s cliché, but Dorian, if you ever stumble across my silly article here, I’m so glad you decided to stick around. I bought ‘Exit Note’ as soon as I found out it had been released and I inhaled it as fast as I could, even leaving a club to scurry round the back for an hour to polish it off. Now it is time for me to yap…

Content Warning: Suicide, Self-Harm, Addiction, Mention of Rishi Sunak.

“So I dedicate this thing, this plea to the soulless Medical Gods, to all my fellow neurodiverse souls, writhing inside the hell of their own heads, kept afloat by nothing more than grit, fury, and bad ideas. I hope it gets better - I hope those bastards give you the help you need, and deserve. And if they don’t? Be loud. Be relentless: Go down fighting.” - Dorian Bridges

Bridges’ book follows Zillah, a neurodivergent junkie who has been kicked out of his flat by his girlfriend Emma, after she’s stabbed by one of Zillah’s used heroin needles in their shared bed. Zillah is sent to his best friend’s, Tom, who cuts him a deal that he can do heroin in his house as long as they use the “buddy system”, where Tom supervises Zillah administering himself with intravenous heroin in the upstairs bathroom. Zillah has been fighting his doctors and support team for a diamorphine script (pharmaceutical heroin) as the methadone makes his brain feel foggy, like his thoughts are being filtered through chunder, and on top of that Zillah “doesn’t do withdrawal”. Withdrawal turns him into a rattling puddle of anxiety and has him “spend more time looking at Tom’s toilet than his face”. Bridges’ writing wastes no oxygen and dives straight into the rough, a characteristic of Bridges’ YouTube channel that I adore. This book was a harrowing and addictive read, at it’s heart it is a beautifully gothic-political-punk-kicking-and-screaming piece about the controversial conversation surrounding addiction, mental health and the public perception of addicts. Both Bridges’ and his character Zillah detest to being called an “addict” much preferring being labelled as a “junkie”, as Zillah states “Frankly I hate it less than ‘addict’. Eurgh. Addict. It sounds so… pathological. Whenever I hear that word, I see some disapproving Tory face, like… like Theresa fucking May, announcing that “All addicts are to be socially cleansed, this Wednesday”. That’s what I hear.”

Zillah’s fight for diamorphine sounds controversial at first, giving heroin to heroin addicts, but there have been trials for supervised injectable heroin for treatment-resistant patients, as in, patients who have tried all of the avenues for their addiction and nothing has helped, not the therapies, the methadone scripts, the anti-depressants. Nothing. A diamorphine script for suitable patients should not be this much of a struggle, a war, for junkies who are desperate for help. Small studies present evidence that pharmaceutical heroin has similar or higher rates of success in reducing the frequency in which patients are using street heroin. Diamorphine can be an effective treatment for heroin-dependent patients that do not improve through other treatment plans. (Here’s a Cambridge review of multiple different studies, that can explain this better than I can).

‘Exit Note’ sparked an incurable rage within me, watching Zillah be failed by everyone who was supposed to help him only made me more vehemently oppose the tory party, as Zillah’s experiences echo Bridges’ personal experiences trying (and to this date — still failing) to get the life-saving diamorphine script he needs. In the foreword, Dorian Bridges hopes that he “may finally be understood by my doctors, and I will, after fifteen years in drug services, actually be helped.” This is a common experience that ensnares a lot of people that try and access the UK healthcare system. Our prime minister, Rishi Sunak — remember kids, this is the guy who bet on human lives with Piers Morgan — will turn around and blame industrial action for the ridiculous waiting times, instead of his own budget cuts. Zillah, whilst arguing with his sister, Cindy, about needing a diamorphine script the morning after he was punted out Emma’s, gives a speech saying that “…[I don’t see] why I shouldn’t be around to see it, why I should be left to overdose in a ditch, all because the medication I need - which is used in hospitals every minute of every day, with zero negative side effects besides constipation and a bit of nausea - is being barred to me by outdated, obscene fucking Tory law-makers!”. This is the core of Zillah’s fight, the plea that so many people suffering under our health service have to face every single day, fighting with doctors who refuse to listen, who refuse to give patients the care they fucking need to survive. It is nothing short of dehumanising that due to tory budget cuts and old-fashioned views, not just about addiction and mental health, but also transphobia and misogyny, prevent the sick in Britain from getting help. People are being forced to wait for the older generation to die out before we can get help, to face doctors who simply don’t believe they are sick, who will tell people “it’s all in their head” for years until their organs are cemented together from endometriosis, who will label junkies and addicts as “drug-seeking” and banish them from their offices to fend for themselves. Transgender patients face GPs that won’t even refer them to the gender clinics they LEGALLY are required to refer them to. The rife discrimination within our healthcare system fails so many people before they’ve even began to get help. I know too many anecdotes about what a nightmare it is for people to access the NHS. I have friends who have had their hypermobility blamed on their periods, I know someone who developed serotonin syndrome after being put on antidepressants and their doctor was so neglectful that they were wrongly advised to take double their dose instead of coming off their meds entirely (serotonin syndrome can be fatal, and we need to call cases like this what it is. Pure. Medical. Negligence.) I have no other words to say other than I am horrified that our NHS is so inaccessible and for many, our glorious NHS amounts to the greatest fucking disservice they have encountered in their lives. God bless the NHS!

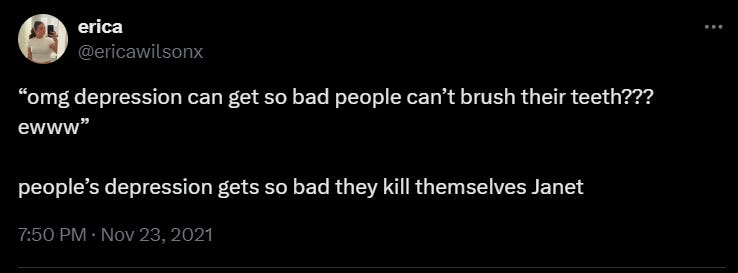

As Zillah continues to argue with his sister Cindy, she remarks that Zillah’s life has been a “bloody waste… what a bloody, bloody waste of your potential!”. Zillah’s response to her dug it’s thumb into a wound I didn’t realise I had… “I get it, you hate my job, you think it’s stupid, you always will, and I really don’t care… getting back to the subject of saving my life, however - please?”. The first time I read this line, Dorian Bridges cemented a place in my heart with this book. I saw a little piece of myself within this conversation with Cindy, as Zillah pleads that he needs HELP instead of criticism. At some of my lowest points whilst trying to reach out I felt like the people around me focused on the most ridiculous things instead of the bigger picture: I was spiralling and needed intervention (NOT to be told I need a job or to try take a fucking bath with a cup of tea). I know Zillah and I are not alone in this experience, the current climate surrounding mental illness is a catch 22: the general population will “accept” mental illness until your symptoms become unsavoury. This sentiment bleeds into everything; In the way the public perceive the homeless in Britain, to “not give them any money because they’ll spend it on drugs” (as if this is a moral failing on their part, and not a direct response to the corrupt system that allows any of us to be living a sub-human existence), the way drug addiction is not seen as the mental health issue it is, the way different routes of administration are stigmatised over others (because rich white people LOVE snorting cocaine… but black people are scrutinized for smoking crack, when it’s the same drug…) how self harm is viewed as “attention-seeking” (and so what if it is? do you think healthy people purposely inflict physical pain onto themselves?), eating disorders are glorified — that is, until you don’t have a “pretty” one — and how for a lot of us, our own parents will blame us for “not trying hard enough” when we are doing our bloody best at just trying to survive. Like Zillah, too many of us are failed by those around us, are left unsupported until we try and end our suffering, and then just to rub salt in the wounds we are then blamed for not reaching out, (“you know you can always talk to me!”) as if society ever REALLY gave us that option to begin with. It’s all smoke and mirrors.

In my personal life I have seen how people of the older generation view addiction, and how they will be the first to demonise junkies instead of our real mutual enemies. My step-dad has Parkinson’s, and before work a few years ago whilst trying to get his script from the pharmacy he was turned away because “some junkie was getting his methadone”. I remember being fifteen hearing those words come out of my step-dad’s mouth, and noted how he viewed his own medication as “more important” in the way he spoke about that story, going as far to cite that his Parkinson’s medication was time-sensitive, completely disregarding that methadone is also a time-sensitive medication. It’s no secret that our society runs better when there’s class infighting, if you blame the junkie for not getting your medication you don’t need to look at the NHS failure, that people, even once they’ve jumped through all the hoops to actually get seen and diagnosed, still run into issues with getting their prescriptions. I don’t blame my step-dad for having this reaction, addiction is seen as a choice. Even within medical fields addiction is labelled as a choice, as many cite the “choice theory of addiction” to fuel their bigotry. “In choice theory the only reason why an individual returns to addiction is that they have decided to do so. They are fully responsible for the relapse and it will be up to them to once again quit addiction if they choose to do so.” This stigma harbours violence towards addicts, and prevents people from facing the music and realising that addicts are mentally ill and deserve help, deserve medication the same as everyone else. Whilst Zillah is discussing his diamorphine plight with Emma, she brings up a story he told online about being so desperate for heroin, that he collected old blood clots from his used needles and shot them up, with Emma stating that that behaviour wasn’t normal or safe. Zillah cracks and says “Do you even know what a mental illness is, Em? You get that we look like people and talk like people, pretty fucking intelligent people, sometimes, but there’s a pretty big part of us that is actually completely crazy?”. Zillah is acknowledging a cognitive dissonance between knowing addiction is a disease and understanding it, Emma is not fully realising that Zillah’s actions are one of a mentally ill individual, despite knowing addiction is a disease, and should not be chalked up to someone simply just “looking for a fix”. Addiction is viewed similarly to self harm in that it is mythologised into a thing that someone does to themselves rather than a symptom of an underlying problem, or something a person is suffering from.

After being denied diamorphine for a final time, Zillah attempts to become a martyr for the drug war, as he films a suicide video in Tom’s upstairs bathroom. Zillah, forcing the world to acknowledge his pain, is seen with a self-inflicted “DRUG WAR MARTYR” lacerated across his chest. He explains to the camera why he is killing himself; he can’t get diamorphine, he has been getting street heroin instead to self-medicate, the NHS will not help him. He explains that he got a dodgy batch one time, and it sent him into psychosis. He felt that spirits were calling for him to hurt his own mother with a claw hammer, and he had to be institutionalized for 2 weeks until the effects wore off (he states in the book that his symptoms aligned with being a “paranoid schizophrenic”). This is precisely why so many people advocate for full legalisation of drugs, criminalising drugs has never once stopped someone from taking them, it just puts people in danger (prohibition in the USA is a brilliant case study for this, I’ve linked a paper that shows during prohibition alcohol consumption actually increased in the US). Full legalisation keeps people safe, it stops people from dying. Full legalisation of drugs stops people falling into the same situation as Zillah, where mentally ill people looking to fix themselves wouldn’t have to risk their own lives, and others around them, if they could get clean, pure, pharmaceutical grade drugs. Prohibition is proven to be expensive and counter-intuitive, making drug use illegal only prevents any useful legislation around how drugs are distributed, where they are distributed from, and who is allowed to take them. If you live in the UK, you no doubt grew up around 15 year olds popping eccies on the weekends. I was unfortunate enough to know two people who died because of this during high school. Both of them would still be alive today if the drugs they were taking were safe and regulated, who knows if they would have even had access to them if they couldn’t be bought from some random cunt that doesn’t ID?

Zillah’s video is uploaded to YouTube before he makes an attempt on his life and lands himself in hospital, in a 5 day coma as his team of doctors fight to keep him alive. Zillah’s attempt, strangely enough, validated a lot of my own feelings about my mental health. Whilst reading about his attempted martyrdom, and the subsequent fallout of his friends and family feeling defeated whilst he recovered in the hospital, ‘no good alone’ by Rayne Fisher-Quann vibrated in my head. Martyrdom may not be my speed, but Zillah’s desperation isn’t unique. In Fisher-Quann’s essay, she details how modern wellness culture promotes social isolation instead of community: “…ritualistic self-punishment and pathetic martyrdom were the only ways I [she] could ever make myself worthy of other people.” This line from Fisher-Quann encapsulates Zillah, after all he literally tried to off himself in his best friend’s bathroom. Throughout the entire book it is made apparent that Zillah isn’t one for reaching out for help: when his heroin relapse started he kept it under wraps for two months before Emma found out, when he talks to his sister she retorts that she never knows what’s going on with Zillah (in fairness, as soon as he spills his guts she threatens him with hospitalisation and says he’s wasted his potential, so I don’t blame him too much…) and despite Tom’s “buddy system”, Zillah still uses secretly throughout the day. I understand Zillah. I understand feeling so fucked up that I don’t want my friends to see me, I understand the comfort of isolation when I lie to myself and say I’m “saving” my friends from myself (I implore anyone who has ever, even once, felt this way to go and read no good alone. You won’t regret it, I promise). I understand feeling suicidal and thinking it would be less burdensome on everyone around me to just remove myself from their lives. Reading on paper someone else verbalising the thoughts and feelings I have about my neurosis struck a chord in me I don’t think I can ever unhear. No good alone put the idea of actually reaching out for help in my head, and reading Zillah’s attempt hammered the nail into the coffin. Rayne Fisher-Quann puts it: “It is a cruel and fundamentally inhuman tragedy that the culture has convinced so many of us that we must be healed in isolation, because being surrounded by people — people who love us, or care for us, or are willing to sit in the same room with us while we clean up our messes — is about the only way that I, for one, have ever been able to get better.” Zillah only gets better with help from his friends and family. When he’s in hospital, they fight tooth and nail for him to get him the diamorphine and the help that he needs and deserves. I’m glad that, despite all the hurt Zillah unfairly deals with in his life, that it concludes through him getting help from someone else. Relying on community should never feel overplayed, cliché, or “not worth my time”. No one is an island, no matter how hard society and our own government pushes that narrative (see tory party members arguing that the poor should just “pull up their bootstraps”…) What I’m saying is, ask your friends to hang out for a bit instead of locking yourself in your room. Please don’t intentionally make yourself miserable because you’re too proud to accept help from others. (I love you, reader. If no one else in your life thinks you deserve help and support, I promise, I think you do. You deserve it more than anyone).

‘Exit Note’ is a book I didn’t know I needed to read, and has been a brilliant lens to shove my pre-existing anti-tory, pro-legalisation and destigmatising addiction opinions down my friends’ throats (sorry to everyone I went clubbing with last weekend who pretty much only heard me yap about this book). I think ‘Exit Note’ is a great way to get people talking about addiction, and to begin dismantling the notion that drugs and addiction hold any moral ground. For me, the fact Dorian Bridges is from the UK and the book discusses Zillah going through the NHS specifically, I think is really valuable as our media is very focused towards the USA; I know myself I’m more well versed in American politics than I am with UK politics, which only makes UK-based media all the more valuable as we don’t like to talk about our own politics, even when it does affect us.

I truly hope that Dorian, along with everyone else fighting for their lives, gets the help they need and deserve. No one deserves to feel unheard, least of all to be told to bugger off and not be helped when they are SICK. Medical care is one of the most basic human rights. I am so sorry if you reading this have ever had this right stripped from you. As Dorian puts it: “Be Loud. Be Relentless: Go down fighting.” You deserve to be heard. You deserve to be helped. Good luck.

haiii :3

This is my first article guys… tell me what you think… like + subscribe…

Here’s my club fit + better photo of the shorts I made myself as a wee bonus for everyone who read my essay :D

Excellent...

that was beautiful and very heart felt. a lovely read 10/10 keep it up -will:)